Percutaneous cholecystostomy

This 60 year old woman presented to the ED with a several-day history of abdominal pain and fever.

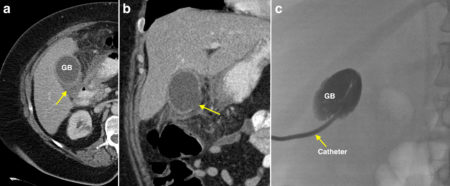

An abdominal CT was performed, which showed thickening of the gallbladder wall and some pericholecystic fluid (arrow on transverse CT image (a)), indicating acute cholecystitis. In addition there was a defect in the medial aspect of the gallbladder wall (arrow on coronal CT image (b)) due to perforation, which is an uncommon complication of acute cholecystitis. The patient was referred to Interventional Radiology for a percutaneous cholecystostomy.

In the setting of perforation, laparoscopic cholecystectomy is not a suitable treatment option however even open cholecystectomy can be extremely difficult due to the extensive inflammatory changes around the gallbladder and friability of the gallbladder wall – the mortality rate associated with open cholecystectomy in patients with perforation is much higher1.

As a result, percutaneous drainage of the gallbladder (cholecystostomy) in Interventional Radiology is now widely used in the initial treatment of perforated acute cholecystitis. It is also used in patients with cholecystitis that is uncomplicated but who are unfit for surgery for other reasons such as systemic comorbidities or old age. While the drainage catheter can be left in situ indefinitely, percutaneous cholecystostomy is often used a bridging treatment to allow the acute process to resolve following which an elective interval laparoscopic or open cholecystectomy can be performed.

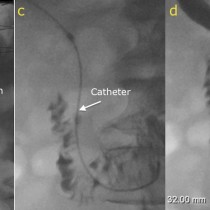

The procedure is safe and straightforward. Using ultrasound for initial guidance, an access needle is advanced through the liver into the gallbladder. A guide wire is inserted through this needle, after which the Interventional Radiologist switches to fluoroscopic guidance, and a small gauge (usually 8 French) pigtail catheter is threaded over the wire into the gallbladder. In image (c) here, the catheter (arrow) can be seen entering the gallbladder, which has been opacified with iodinated contrast injected through the catheter.

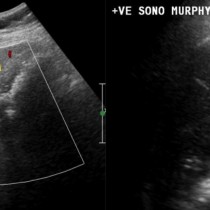

An important footnote in this case is that CT is not the preferred initial imaging modality in suspected acute cholecystitis; instead, ultrasound should always be the first-line imaging test. However, in many cases (including this one), the patient’s symptoms and clinical signs may be non-specific and if other acute abdominal pathology is also high in the differential diagnosis then CT is a reasonable first step. The gallbladder wall thickening and pericholecystic fluid visible on this patient’s CT would also have been identified at ultrasound; in addition, ultrasound would have shown the causative gallbladder calculi (often not visible on CT).

As a reminder, the potential complications of acute cholecystitis include:

- Empyema

- Gangrene of gallbladder wall (leading to perforation)

- Haemorrhage into the gallbladder (haemorrhage cholecystitis)

- Pericholecystic abscess

- Portal vein thrombosis

- Liver abscess

Reference:

- Percutaneous transhepatic gall bladder drainage: a better initial therapeutic choice for patients with gall bladder perforation in the emergency department. CC Huang et al. Emerg Med J. 2007 Dec; 24(12): 836–840. doi: 10.1136/emj.2007.052175